Boston Landmarks Orchestra: A Mission of Public Service

Listen

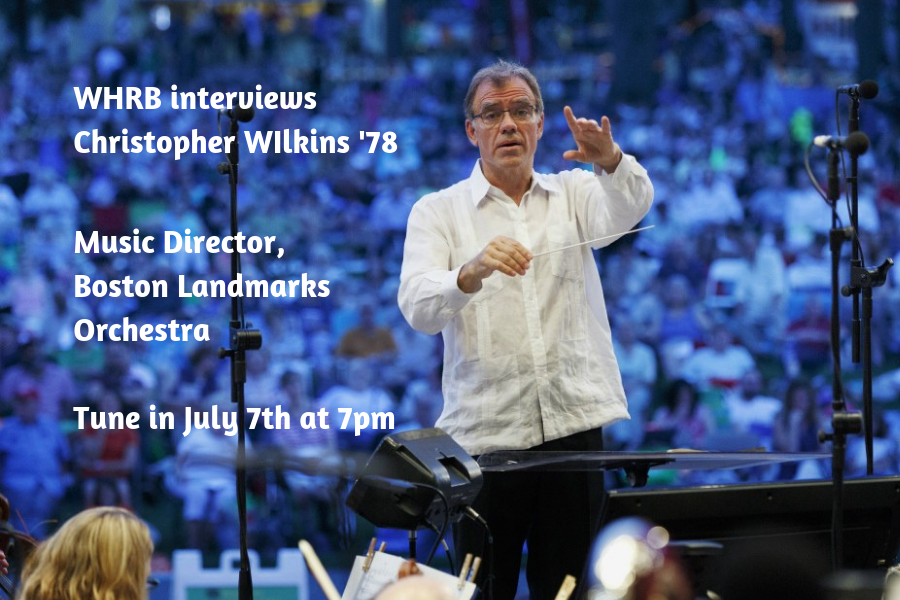

Join WHRB Classical as we speak with Christopher Wilkins, the music director of the Boston Landmarks Orchestra. This summer, the orchestra's series of free outdoor concerts at the Hatch Memorial Shell includes a tribute to the 50th anniversary of the moon landing presented with the Museum of Science Hayden Planetarium, a feature of songs and spirituals of African-American composers presented alongside a series of panels and discussion about representation in music, and a collaboration with the New England Aquarium which will raise awareness of climate change. Listen to the full interview above, or read on for an excerpt.

Pao: If your concerts are somewhat political in that they engage with topics such as climate change or race relations, are you ever worried that you will scare away listeners?

Wilkins: That's a great question. I don’t think you can do both. You can’t dive into these important issues and not create controversy, and not make some people uncomfortable or angry at you. But it’s in the DNA of this orchestra. I’m not the founder. The founder was Charles Ansbacher, who believed deeply in the role of public art in society in general. He wanted to use orchestras as a gathering point for communities, as a healing device. He did that in unbelievable places that were still smoldering from war, including Sarajevo at the end of the Bosnian War. Charles came to Boston and founded the Boston Landmarks Orchestra thinking about, how can we create public service through this institution? Neither Charles nor his wife have ever shied away from controversy or topics that are incendiary just because they didn’t want to offend people. We are here to engage with the important issues of our day. The wonderful thing about music is that it tends to be a safe terrain. People can come to our concerts. We’re not engaging the brain so much: we’re mostly engaging the heart, and people’s sensibilities of compassion and empathy, and just the deep pleasure that comes from sharing these beautiful experiences. We are giving a whole lot of children the chance to not only enjoy the music but to play onstage with us, and often their first chances to ever be on stage is with us. We often commission works specifically so that community members can perform with us. I think most people, regardless of what we’re talking about, I don’t think anyone has any trouble understanding what we’re doing and why. The more they understand that mission, I think in general, the more excited they become to support us…

Yo-Yo Ma recently said, “there is no such thing as apolitical music-making.” I think that’s a basic truth. Every time you’re out there, you are presenting a point of view. You are signaling some kind of cultural indicators. Who wrote the piece? Who was it intended for? Who are you on stage? How are you presenting it? Who feels welcome at this concert, and who feels like an outsider? All of these things, I think we are often unconscious of when we perform, but they’re there. We try to look at all those questions very closely and make sure we’re presenting as broad a perspective as we possibly can, because we want to represent all of Boston.

Pao: Today [this interview aired at 7pm on July 7th], we’re listening to a piece by Amy Beach that your orchestra performed in 2018. Why is Amy Beach important to you?

Wilkins: Amy Beach is the ONLY name of a woman on the Hatch Shell. There are 76 names in gold-colored lettering attached all around the Hatch Shell. This was an idea championed by Arthur Fiedler when he was performing with the Boston Pops at the Hatch Shell. For decades, it was all white men. Amy Beach’s name was added, and John Williams’s name was added, but I think the list is still unfortunate. I don’t say this too often, Allison, but for your listeners, I’ll say this: I think that the idea to add their names was probably exciting at the time, and in a way it did show the range of repertoire that the Boston Pops advocated for. But today it looks hopelessly dated to me, because it flies in the face of exactly what we’re talking about. How can you have 76 names up there with only one woman and no person of color? It’s the wrong signal. But anyway, Amy Beach was a very important Boston composer of the turn of the last century. She was a contemporary of John Knowles Paine, Edward McDowell, and many important Bostonians of that era. She is on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, her home on Cumberland North Ave in the Back Bay is marked with a historic plaque, and her name will be celebrated more and more as we approach the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote.

Pao: You graduated from Harvard College in 1978. When you entered Harvard, did you already know you wanted to be a professional musician?

Wilkins: I entered as a pre-med. And then I ended up as an East Asian Studies major for a time. I was totally confused about what I wanted to do. When I was playing oboe in the student-run Bach Society Orchestra as a sophomore, the conductor of the orchestra at the time stepped down and there was nobody else on the scene who had experience as a conductor. I took over that position as a Junior so I had it for two years which was fantastic. Then I entered music school at Yale after that. I wouldn’t be a professional musician if not for Bach Society Orchestra!

Allison Pao is a producer for WHRB Classical. Click here for more information about upcoming concerts with the Boston Landmarks Orchestra. All concerts are free of charge.