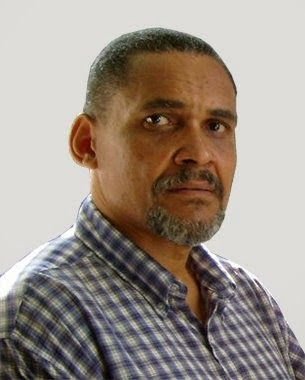

Interview: Jorge Castillo

Listen

An interview with Jorge Castillo, a Cuban poet, writer, journalist, and dissident. He was arrested in 2003 as part of the Black Spring crackdown, where 75 people, including Mr. Castillo, were arrested, tried, and sentenced. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison, but was released for health reasons. Last year, he came to Harvard as a visiting scholar under the Scholars at Risk program and now is at Brown University under a similar program, but is determined to go back to Cuba to continue fighting for freedom of expression and the press.

Note: The interview was done through an interpreter, Rafael Escalera, a history student at Harvard College. The following transcription is entirely in English and is based on the translation Mr. Escalera provided.

Thomas Elliott: We are extraordinarily fortunate today to have Jorge Oliveira Castillo, a Cuban poet, writer, and dissident in the studio today. His work has been published around the world and published in many languages. And for his actions and speech against the government, Mr. Castillo was sentenced to eighteen years in prison, incarcerated in Guantanamo for two years before being released on medical grounds. He is here at Harvard thanks to the Scholars at Risk program, but has promised to return to Cuba to continue fighting for the freedom of speech and expression. We are also joined by Rafael, a history student from Puerto Rico studying at Harvard College, who will be the interpreter for this interview. First question – what drove you to writing poetry?

Jorge Castillo: Even though I was always in literature from a very young age, in reality, what drove me to dedicate myself completely to poetry was the prison I was incarcerated in for two years, especially the time where I was in solitary confinement for nine months with the only company of the bees, the wasps, and the ants. Poetry was a way to cure the solace. And it is completely thanks to poetry and my belief in God that I am able to sit here today.

TE: And you were, and are to a degree, still involved with journalism. So, what brought you to fiction instead of staying with non-fiction?

JC: Well, I really went to prison for founding an independent press called The Havana Press, but what drove me to fiction as opposed to non-fiction was the desire and the need to create an alternative reality, to create a new reality as a means of survival.

TE: And what about long-form fiction, did you see it as a natural development of your writing, a literary evolution, or was is something you got interested in independent of your poetry?

JC: Well, I think they’re very combined. My fiction is inspired by my non-fiction, especially my short stories and my poetry. I am very fond of epiphigrams, for instance, which are very short and don’t have many lines. My short stories are also very short, so my fiction is inspired by my non-fiction.

TE: And you mentioned you were in solitary for nine months and…how were you able to write in prison, given that that’s what got you in there in the first place?

JC: Well, it was very difficult. I asked and was never given neither a chair nor a table, so it was very difficult to write my literature, which, in fact, I had a lot of trouble getting out of prison and I had to do it clandestinely.

TE:What did you draw as an influence during your time in prison?

JC: To start, I have some influences, not that many, but I have influences from Latin America and also from North America. To tell you some of the North American ones, in terms of poetry, there is Walt Whitman, Edgar Allen Poe, and Emily Dickinson. And in short stories, Poe as well and Hemingway.

TE: How were you able to get your published, especially given that the government really doesn’t like you and you had to turn to publishers outside, but how were you able to establish contact in the first place?

JC: At first, it was even more difficult than it is now because there used to be no internet and now there’s slightly more internet. But it was through the internet and through clandestine visits through NGOs or people who were interested, but took a very high risk to come visit that I was able to put my work out. And now, thankfully, I’ve been able to publish eight books, six [of which are] poetry books and two [of which are] short story books.

TE: And I went to the Scholars at Risk writing event the other week and you mentioned something about the Independent Writers’ Association in Cuba. What could you tell us about that?

JC: Well, this was a group I started in 2007 along with a few other poets and, really, the objective is to create an alternative to the official institutions. We’re interested in any type of writer, whatever they may think, we’re just interested in their content and their desire to defend the basic freedoms of expression.

TE: That’s all the questions I have. Thank you very much for coming, it’s been a pleasure to have you. And best of luck on your return to Cuba.

JC: Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure to be here and answer all these questions and thanks to you and to the audience.

Thomas Elliott is a member of WHRB’s Administrative Board and a DJ on the Jazz Spectrum. Tune into the Jazz Spectrum Monday-Friday from 5 a.m. to 1 p.m.