Shaolin Monks on the Mic: Orientalism, Buddhism, and the Wu Tang Clan, Pt. 1

On November 15, 2004, Russell Jones, better known by the handle of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, the wild card of the Wu-Tang Clan, died of a drug overdose at a recording studio in New York City (Zahlaway). The legendary rapper from the iconic supergroup was given the standard hip-hop goodbye: a farewell track from the remaining Wu Tang members. “Life Changes”, from the album 8 Diagrams, is one of the most moving songs in the history of hip-hop, a raw outpouring of grief and emotion from a group that spent the majority of its existence perfecting a hard-edged, ruthless sound. The genre is full of “dead homies” tracks however, and despite this one’s earnestness and intensity, what really sets it apart from the pack is the final two minutes. While most songs commemorating fallen rappers contain references to a Judeo-Christian concept of the afterlife[1], “Life Changes” ends with the sounding of a gong, followed by the recitation of the Heart Sutra (a key Mahayana Buddhist text) by Shaolin monk Sifu Shi Yan Ming, a personal friend of the Wu Tang Clan. The inclusion of Eastern sacred texts in American popular music is nothing new: artists such as the Beatles and Bob Dylan famously have done just that. But for hip hop, a genre typically associated with traditional black Christianity or Islam, to invoke the spiritual teachings of the East is seemingly unprecedented. This essay will seek to explain the reasons why the paragon of hardcore rap groups would draw inspiration from Buddhism.

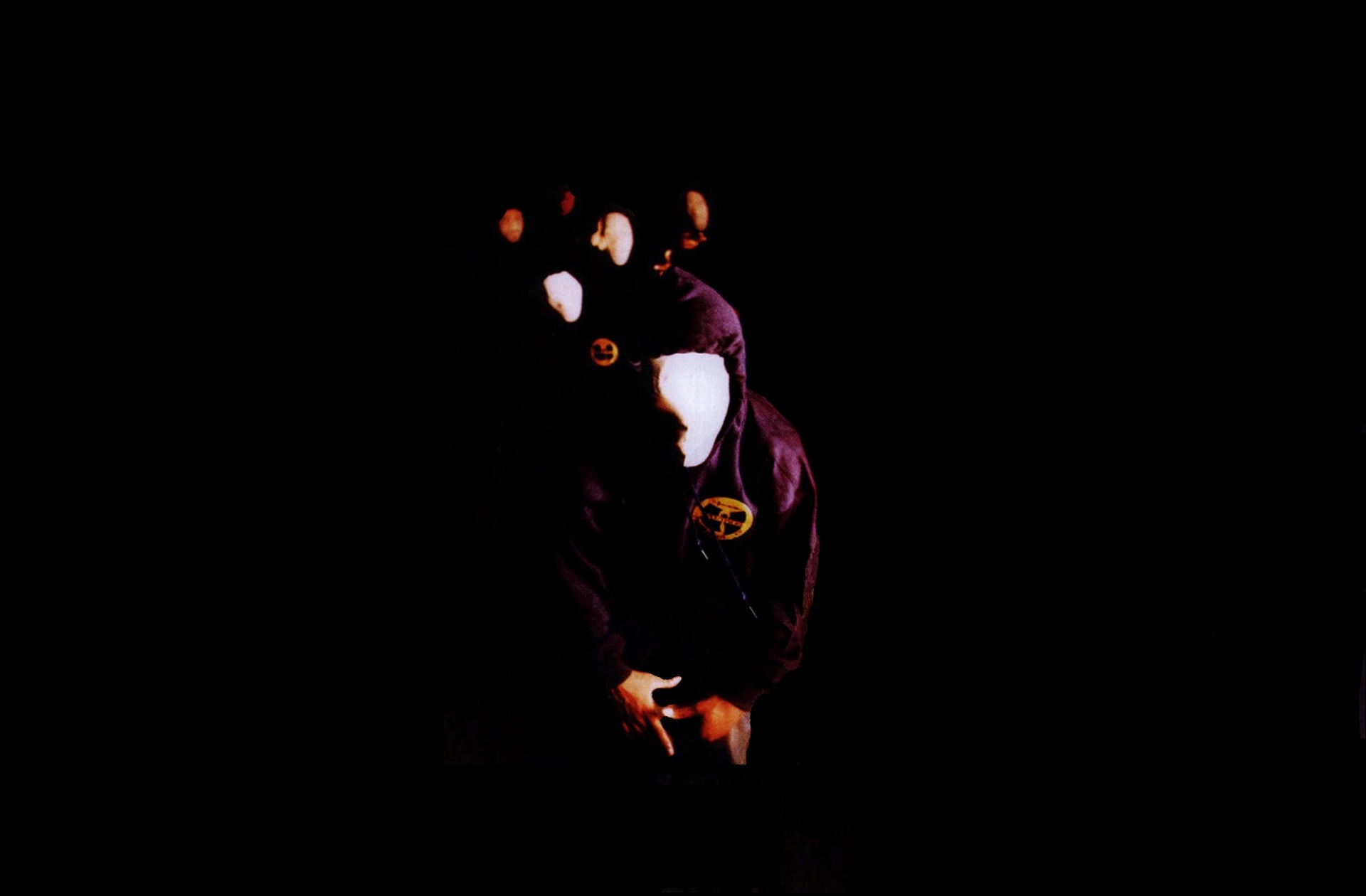

The Wu Tang Clan is notoriously prolific: beyond its releases as a group, there are countless solo albums from its members and a whole cluster of affiliated artists. All these works are unified by an ethos developed by the RZA, the frontman of the Wu Tang Clan, who bears the title of “the Abbot” due to his leadership and wisdom (The Tao of Wu 225). The RZA’s unique artistic vision made the sound of the Wu Tang Clan one of the most distinctive and influential in hip-hop, and his philosophy was the guiding force of the image, attitude, and style of the group. In his book The Wu Tang Manual, the RZA outlines a syncretistic approach to spiritual wisdom in a chapter entitled “The Way of The Wu: The Grand Spiritual Megamix”, where he shares his insights on the teachings of spiritual traditions ranging from Christianity to Buddhism to Taoism (Wu Tang Manual 39). This syncretism is developed further in The Tao of Wu, a book by the RZA in collaboration with music writer Chris Norris, which outlines the life experiences and spiritual journey of the RZA and their effect on the philosophy of the Wu Tang Clan. Scholar of religion Monica Miller refers to the RZA’s synthesis of various influences (most significantly, kung-fu films, comic books, Eastern religions, and the Afrocentric Five Percenter movement) as a “patchwork of poached taos of life”: a conglomeration of wisdom from various sources on how to survive and prosper (Miller 64-65). Miller argues that the RZA used his “poaching” to construct an arsenal of spiritual “strategies” and “tactics” to deal with his life circumstances and help him and the Wu Tang Clan attain success (Miller 65). However, this evaluation of the RZA’s philosophy as largely pragmatic and tactical[2] fails to account for the deeper existential concerns that motivate his creation of a personal system of beliefs. In this essay, we will hone in on these issues, focusing on the contribution of Ch’an Buddhism[3] to the Spiritual Megamix.

In order to properly explore the use of Buddhist (and more generally, Eastern) religious teaching and iconography in the work of the Wu-Tang Clan, we must examine this appropriation of Asian culture by “Western” artists through the lens of Orientalism. A term popularized by postcolonial scholar Edward Said in a watershed 1978 book, Orientalism[4] refers to the distorted perceptions of Eastern culture and civilization in the West, whether they be prejudiced, romanticized, or both (Taylor 2). In fact, Orientalism that views the Orient in supposedly positive terms, as a “mystical East”, still serves to “systematically essentialize and mystify the non-European Other” (Deutsch). The Wu Tang Clan’s highly romanticized “pop culture Buddhism” falls under this category of Orientalism. However, it must be considered whether the Wu Tang Clan’s identity as African Americans from the New York slums, themselves seen as a “non-European Other”, differentiates their Orientalism from that of the dominant white/European American narrative. Through engaging with Asian culture, and specifically Buddhism, the Wu Tang Clan’s syncretistic spirituality goes beyond Miller’s “pragmatic philosophy” and responds to being “othered” by American society by appealing to the “otherness” of the Orient to form a new identity, specifically relating to it by associating the struggles of black urban youth in the projects with the Buddhist narrative of overcoming suffering.

Although Orientalism is typically interpreted as a method of reinforcing Occidental, specifically European, cultural superiority, Orientalist tendencies can also be found in African American culture, albeit in different form. As argued by religious scholar Nathaniel Deutsch, “descendants of slaves… stood worlds apart from European Orientalists in London and Paris who possessed the desire and power to dominate and restructure the so-called ‘Orient’” (Deutsch). We will identify a specific strain of black Orientalism, and explore the way it manifests itself, in two of the Wu Tang Clan’s major influences: the Five-Percent Nation, and martial arts films. Additionally, we will illuminate the intersections between this Orientalism and the elements of Buddhist teaching found in the philosophy of the Wu Tang Clan.

Continued in Part 2!

[1] Notable examples include “I’ll Be Missing You” by Puff Daddy and “The Crossroads” by Bone Thugs-N-Harmony.

[2] Miller compares the RZA’s “more pragmatic” work to fellow rapper KRS-ONE’s metaphysically oriented The Gospel of Hip-Hop, which sought to establish hip-hop as the religion of the future (Miller 56-63, 69).

[3] Ch’an was later exported to Japan, where it became known as Zen (Jorgensen).

[4] It should be noted that Said’s scholarship focused on orientalism as it relates to the Middle East.