Stereo Hideout in Brooklyn: Brahms V. Radiohead

Photo by Emily Spector

Fog spilled out from the back corners of the stage as the Stereo Hideout orchestra soared through the opening theme of Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 for perhaps the youngest live audience the piece has seen in decades. In the very heart of Flatbush, those filling the 3,000 seats of the King’s Theatre were easily distinguishable from the audiences one might find at a more traditional classical performance. Beers in hand, the hipster millennial audience was seated to hear Steve Hackman conduct his 70 minute rock-classical synthesis entitled “Brahms V. Radiohead.”

The work was situated as the second half of a program revolving entirely around this idea of genre-bending “musical metamorphosis.” The concert began with four of Hackman’s smaller scale syntheses of Brahms and Radiohead as well as two Hackman originals: “Vertigo” and “Of Dreams and Designs Suite.” Over the course of this first half, people continually trickled into the hall as both the box office and entrance lines, each curling around the block, slowly fed into the building. It seems that the first half of the program, in a way, served as the “opening act,” during which people could arrive, get comfortable, and become acquainted with Hackman’s musical fascinations.

While the majority of the music presented was brought to life by the Stereo Hideout orchestra, Hackman’s own compositions called upon a number of guest artists to shake up the instrumentation. “Vertigo” brought the ensemble Time for Three to the stage; comprised of two violinists and a double-bassist, all of whom sing, the trio set up at the very edge of a stage already threatening to overflow with artists. Under turquoise and lavender lights, the trio delivered a riveting performance of the composition, capturing the song’s emotional intensity - a deep anxiety, love, and conviction - in phrase after phrase. The final chorus seemed to reverberate in the hall long after the song finished: “Sometimes though, I lose my balance/ My vertigo overpowers, all my doubts, my fear of flying/ She says don’t look down, I’m right beside you.”

However, the piece doesn’t quite occupy an exact middle-ground between the classical and pop/rock spheres, as despite its classical instrumentation, the arrangement seems to lean quite pop-y at times, as does the song structure and harmonic progression. Regardless, the unrestrained violin melodies, at times climbing above the vocals, intone an unmistakable classical romance, and the moments in which the melodic styles of the voice and violin seamlessly intertwine ultimately render this composition a triumph. The piece undoubtedly pushes the boundaries of pop and classical, and Time for Three’s heartfelt, dynamic, and technically stellar performance certainly emphasizes the piece’s stature as something new on the pop/rock and classical scenes.

Following the trio, Hackman brought out the “Stereo Hideout band,” a traditional rock band, to perform a compilation of four more originals entitled “Of Dreams and Designs Suite.” Hackman played keys and sang with the band, performing what was pretty securely a brief pop-rock set as the orchestra took a back seat, providing a simple background texture. After an intermission, the audience settled back into their seats for the main attraction: Brahms V. Radiohead in full.

With this composition, Hackman combines Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor (1882) with Radiohead’s concept album OK Computer (1997) into one epic 70 minute work. Arranged for a full-size romantic orchestra and three solo vocalists (and ornamented by extremely dynamic lighting, which retrospectively seems like an integral part of the show), the piece essentially follows the form of the original symphony. It begins with the orchestra playing a very low, pensive melody in unison, incrementally splitting into more lines before a timpani roll catapults the meandering players into the unyielding, processional first phrases of the Brahms.

With all instruments mic’d and running through massive monitors on the edge of the stage and speaker stacks hanging from the ceiling, the timpani’s already foreboding march seems all the more intimidating as each strike is bolstered by the audio systems. The Brahms is permitted to proceed unaltered for several lines until its first hard stop, which Hackman takes advantage of, inserting the first true rock phrase, for which the orchestra reverts back to monophony. The Brahms, unfazed, picks up where it left off seconds later, before the cycle repeats. Slowly but surely, it seems that Brahms and Radiohead begin to figure each other out, and Hackman begins to bond the musics, weaving them together into one indistinguishable music and then extracting the parts all over again.

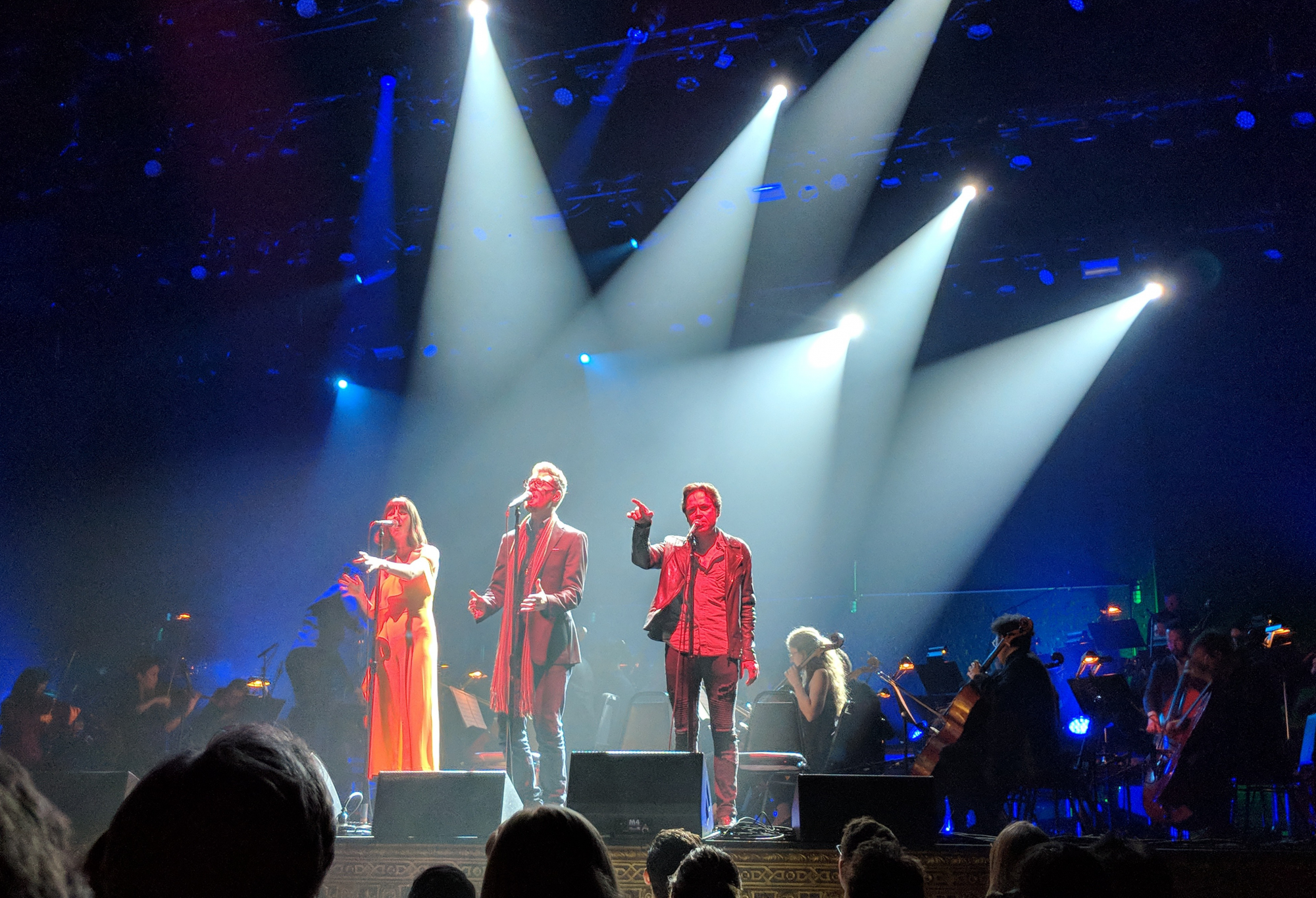

As vocalists Andrew Lipke, Kéren Tayar (an alumna of Boston’s own Berklee College of Music), and Will Post step up to their microphones, the lights surrender their hot red and pink hues in favor of a cooler atmosphere of purple and green. The opening melody of Radiohead’s “Paranoid Android” in Lipke’s voice soon takes precedence over the symphony, and Brahms’s harmonies and figures adapt and evolve to its presence. As Tayar and Post join in, the texture swells and in many ways seems to approach that of a musical theatre song - something magical with great height to it, technically pure and impenetrable, carefully cultivated and deeply emotive.

As the piece progresses, Hackman makes use of the hard stops and distinct foreground trades that dominate the first few minutes of the piece in addition to periods of synthesis when even someone well-versed in both the original symphony and album might find themselves uncertain of what has been altered and how.

Students of music history learn that the classical performances of today are far more tame than they used to be. In Mozart’s era, people might shriek for their favorite singer, chat through an entire opera, or even leave for a snack during an “Ice Cream Aria.” Liszt had to navigate crazed crowds who would tear at his clothing and fight over strands of his long hair. Today’s classical audiences are rigid by comparison - a far cry from the crazed fans outlined in history books - and though Hackman’s music diverges from the classical tradition, he did manage to invite that excitement back into the seated concert hall. The audience was openly receptive and energetic, applauding wherever they deemed fit and hanging on to every note.

While the show was undoubtedly a wildly successful spectacle, I do wonder if its scope was too broad. The first half of the concert seemed to lack focus with its various ensembles and guest artists and Hackman jumping from role to role, sliding around from arranger to composer to performer to frontman rockstar and back again. Although Hackman is certainly capable in all of these positions, it was a bit confusing to compress them into the same half of a program in a concert advertised as a Brahms V. Radiohead exploration.

He is billed a musical renaissance man; his program biography reads, “He is at once a composer, conductor, producer, DJ, arranger, songwriter, singer, pianist, and even rapper,” but his own compositions and participation as a pianist and singer seemed out of place Saturday night, disrupting an otherwise unified program. A part of me wishes he had left those two pieces out out, though they were very well done. To my ears, the span of his musical competence is clear in his arrangements, and explicit proof of his breadth of ability is unnecessary. There are countless examples of miserably fumbled attempts at this type of rock-classical musical fusion, and Hackman’s facility working from both ends of the rock/classical spectrum is obvious in these successful musical syntheses. To do what he does as an arranger necessitates that he be every one of those things listed in his biography, and the audience knows it.

Listen here, to Brahms V. Radiohead, a colossal, forward-looking work offering to both please the ears and the minds of any audience it should come across: https://soundcloud.com/stereo-hideout/sets/brahms-v-radiohead

Emily Spector is a producer for WHRB Classical.